By David R. Beatty C.M., O.B.E.

An effective Chair is absolutely central to building a value-added board. The responsibilities of a modern Board Chair have evolved significantly in the past decade, and so too must the individuals who now hold the post.

There are three essential components of the Chair’s role:

1. Talent: ensuring the board has the right skills to be effective

2. Tone: finding the balance between trust and tension

3. Time: managing the scarcest board resource

Taken together these three “T’s” will determine the governance outcome for all the stakeholders.

Conducting Without a Score

Think of the Chair of a modern, publicly traded company as the conductor of an orchestra filled with world-class musicians but with no score to play from. Beautiful music is a distinct possibility; but so is disharmony and chaos. An orchestral score integrates everyone’s talents in the creation of beautiful outcomes. For the Chair of a Board, the ‘score’ is not fixed but dynamic and complex.

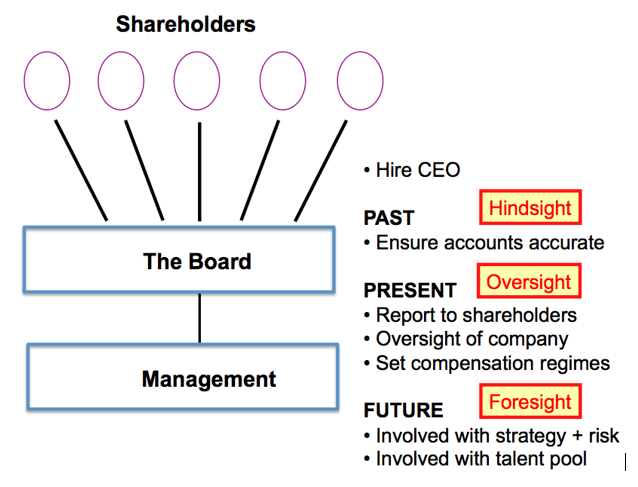

The basics of a Board’s job are well known and well documented. At the top of the heap is the (hopefully-occasional) task of selecting the CEO. Get this one wrong, and very little good will emerge from the board, and it can take three to five years to recover from an unfortunate choice. Once a capable CEO is firmly in place, three time dimensions define a Board’s ongoing role: Past, Present and Future. These timelines can also be thought of as Hindsight, Oversight and Foresight.

1. Mobilizing Talent

The Chair must, over time, build the Board’s capacity to add value. That means not simply enlisting independent directors – ‘gifted amateurs’ — but directors who have a collective set of skills that serve the business’s interests well.

For example, a bank board ought to include at least one director who has specific skills in financial risk management, and a mining board ought to have one or more directors who understand some aspect of mining or have lived in a different culture. Three tools can help in this quest.

Develop a Skills Matrix. The starting point is to develop an ideal representation of the collection of skills needed in the boardroom and then move. Reverting to the orchestration analogy: without a percussionist, it would not be wise to embark upon Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture.

Install Board Evaluations. Once the Chair has attracted directors to fill the skills gaps, the next task is to create an atmosphere of continuous improvement. One instrument that can help to achieve this is an annual Board evaluation: an annual review of the Board’s performance across a number of subject-matter areas, from operational oversight to individual committee performance.

Consider Peer Evaluations. Some boards supplement the overall Board evaluation with an individual peer evaluation, allowing each board member to reflect upon the contributions of the other members against a set of questions. A possibly less threatening technique is to have the chair meet annually with each director one-on-one

At the end of the day, it is the Chair’s responsibility to lead in the attraction and deployment of talent in the boardroom. If the Chair is not vigorously involved in these tasks, the Board will founder and will have virtually no prospect of protecting value — let alone helping to create it. Think about it: are there any world-class orchestras without a world-class conductor?

2. Setting the Tone

The Chair must set the tone: the balance of trust against tension. Trust must be built in many directions in order that the board can do it’s job of testing, probing and questioning.

Trust must be built across three fronts

a) Between the directors around the Board table;

b) Between the Chair and the CEO; and

c) Between the directors and the top management team

If talent is the necessary pre-requisite of all world class orchestras then trust is the ‘invisible glue that binds the individuals together. No trust, no symphony.

(a) Build Trust Between Directors: There is no substitute for the Chair investing time in polling individual directors on a frequent basis to determine their concerns and views on various agenda items. The very individuality of directors – those unique qualities that made each so attractive as a board candidate – also means that each will have a different set of frames and filters through which they view the world. This diversity of views is essential in a value-added board, but unless acknowledged and understood by the Chair, could easily turn a discussion around any issue into a chaotic jumble.

Great conductors listen very well and, in the music world, are the only members of the orchestra who make no sound.

(b) Build Trust between the Chair and the CEO: The Chair must also spend hours with the CEO discussing both the external and internal environments in which the company is operating and the challenges facing the management team. If the Chair/CEO relationship sours, one or the other must in the end depart. Likewise, if the conductor and the lead violinist are not on speaking terms and or do not respect each other professionally, disharmony will prevail.

(c) Build trust between the board and the management team: the broader board/management interface also requires considerable attention. Because the boardroom is such an unnatural and inhibiting environment, social functions should appear frequently in the annual calendar in order for the directors and the top management team to build relationships outside of the board environment. Personal contacts in non-formal settings build relationships that can survive the tensions in the boardroom itself.

In the end, trusting relationships are the bedrock of every board’s ability to add value. Trust takes time and hard work to establish in the first place — and is even harder to maintain in the medium to longer term. And trust can be lost in an unfortunate minute. It is the Chair’s unique responsibility to ensure that trust grows between the directors, with the CEO and across the management chasm.

The Chair must manage tensions within the Board and between the Board and management. Because the Board has fiduciary responsibilities to the company and because carrying out these responsibilities often entails probing questions and deep-dive enquiries, tensions are bound to arise. A board can only be effective if it maintains cordiality with the management team in spite of this. The tone must be one of ‘constructive challenge’, and it is the Chair who must manage the appropriate level of tension, dependent upon the issue at hand and the company’s condition. Following are some approaches that a Chair can use to achieve this:

(a) Pulling out of individual directors their ‘true’ concerns — concerns that might be compromised by group-think both before and during the meeting. It is a best practice for the Chair to call each of the directors prior to the meeting to determine such concerns and then, at the meeting, to ensure that these views are expressed and examined. For example, if the Chair knows Director A has expressed strong reservations about a particular investment in one-on-one discussions prior to the meeting, the Chair must ensure that Director A expresses those concerns at the meeting itself. This is particularly necessary in the case if Director B started discussion on the topic at hand by expressing profound support.

(b) Calming-down behaviour in the boardroom that tends towards the dysfunctional. Strong and experienced directors have strong and often divergent points of view. On most occasions these ‘constructive challenges’ are delivered in a calm and measured manner; but when they are not, it is the Chair’s responsibility to call a time-out and regroup.

(c) Keeping Board discussions focused on the decision at hand and the fact base underlying the decision. Discussions in a room of 15 to 20 people (directors and management) do have a tendency to wander. The Chair must exercise the discipline to keep the discussion ‘on track’ — however broad that ‘track’ might be.

Likewise, when an orchestra conductor finds some sections ‘off track’, he stops the music, re-establishes control and begins again.

Tone, then is a balance between the trust around the boardroom table and the tensions that inevitably occur around that same table. The Chair is the ‘tonal’ manager of the board’s endeavours.

3. Investing Time: the Board’s Scarcest Resource

The Chair is responsible for investing the time of the Board. He or she is responsible for ensuring that the shareholders maximize their return on the directors’ invested time. Typically, directors spend up to 200 hours per year on a major board – preparation plus participation. While this number has increased over the last decade, it is not likely — except in a crisis — to expand further.

The basics of a Board’s job are well known and well documented. At the top of the heap is the (hopefully-occasional) task of selecting the CEO. Get this one wrong, and very little good will emerge from the board, and it can take three to five years to recover from an unfortunate choice.

Once a capable CEO is firmly in place, three time dimensions define a Board’s ongoing role: Past, Present and Future. These timelines can also be thought of as Hindsight, Oversight and Foresight, as shown in Figure One.

Figure One: Board Timelines

In 2004 The Canadian Coalition for Good Governance did a survey of Directors with McKinsey & Co. Each director was asked how his/her board spent their time today and then how they felt the should invest their time. The result was that time spent on the FORESIGHT functions should be doubled:

| Today’s Allocation | Ideal Allocation | |

|---|---|---|

| Hindsight | 40% | 20% |

| Oversight | 40% | 30% |

| Foresight | 20% | 50% |

The Chair must manage these time allocations and from the survey many effective “tools” emerged:

1. Develop a strategic orientation:

- Build a one/two day off-site strategy session into the annual board meeting calendar

- Get new directors into a rigorous orientation program and

- Continuously learn about the business i.e. analysts reports, field visits, conferences, regular updates from CEO, etc

2. Start every Board meeting with a CEO update that focuses on the strategic positioning of the company:

- “What’s different in the environment since we last met?”

- “How our strategy might be adjusted in response – if at all.”

- “Things I am looking out for.”

3. On major items, have the CEO prepare a one-page covering memo that outlines his/her proposal and the three main reasons why this makes sense PLUS the things that caused most concern to him/her in arriving at this recommendation. This helps focus director attention within the reading materials and ‘legitimizes’ debate and discussion without threatening the CEO’s authority to come to a final decision.

4. Reviewing the effectiveness of the meeting with the directors ‘in camera’ following each meeting, and then working with the CEO to rebalance the agenda for the next meeting

In short, the Chair is the Board’s timekeeper and investment manager. He or she must work continuously to keep the agenda on track while opening up as much space as possible for discussion. In survey after survey, Boards have said they want less presentations and more time to simply discuss the matters in front of them.

In closing

Just as the keys to general learning are the ‘three Rs’ – reading, ‘riting and ‘rithmetic – so the keys to a value-added Board are the Chair’s active management of the three Ts – talent, tone and time.

It is time for the ‘governance conductors’ – the board chairs to take control of their unscripted virtuoso players and lead their ‘orchestras’ to more harmonious outcomes.

Professor David R. Beatty, O.B. E., is the Chair of the board of Inmet Mining (listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange) and is a member of the boards of FirstService Corporation of Toronto and Walter Energy of Birmingham, Alabama.

He has served on over 35 boards in Canada, the U.S., Australia, Mexico and the UK. Over his career he has been Chair of seven companies.

Professor Beatty is the Conway Director of the Clarkson Centre for Business Ethics & Board Effectiveness and Professor of Strategic Management at the Rotman School. He was instrumental in both the development of and the teaching of the Directors Education Program in Canada and he was the Founding Managing Director of the Canadian Coalition for Good Governance.

In June of 2010 he co-chaired the Annual ICGN Conference in Toronto.